Mon:06-12-06 Mon:06-12-06

Interview: Destroyer

Story by Matt LeMay Six years ago, on a whim, I took home the ugliest CD in the whole record store. Thankfully, that CD was Destroyer's Thief, a delightfully warped and lyrically complex pop record that would gradually become one of my favorite releases of the year. Since then, Vancouverite Dan Bejar has released four more records as Destroyer, each one expanding both his stylistic oeuvre and his devoted fanbase. I conducted an e-mail interview with Bejar following his successful co-headlining tour with the Magnolia Electric Co., in which he talked about touring, precision, transcendence, elements of songwriting, and the Destroyer Drinking Game. Pitchfork: You're working on Swan Lake, a project with Spencer Krug from Wolf Parade and Sunset Rubdown, and Carey Mercer from Frog Eyes. Have you recorded anything yet? Who's the alpha male? It's actually really hard for me to imagine the three of you working together, since you all seem to write songs that are pretty conceptually tight and distinctive. Dan Bejar: Well, Spencer and Carey have a long history of working together-- they also both played in Destroyer when we toured Europe last year. Musically, they're pretty in tune with each other, and I think go for a lot of the same kind of sounds and arrangements. I just brought some songs to the table, played a little bit of functional guitar on them, and [did] a bit of singing on their songs in spots they guided me to. I totally trust and am a fan of their instincts, and they both have way more experience with recording than I do, so to relinquish "control" over my songs was an easy and enjoyable and necessary thing to do. The fact that I have no real idea what this record sounds like is a testament to who the alpha males are in the project, if you're gonna look at it that way. Pitchfork: I assume you've seen the Destroyer drinking game. My personal favorite item on that list is "moment of unexpected sweetness." You have a way with re-contextualizing lyrics that might otherwise really seem trite and obvious. Do you pace yourself with more obtuse lyrics and more direct lyrics? DB: I like putting common expressions next to uncommon expressions. I'm sure in Poetry 101 there is a name for it, but it seems like you usually go one way or the other in rock music. I'm not that conscious of my writing, so pacing the lyrics doesn't really enter the picture. Moments of unexpected sweetness happen when romance enters, which always happens in songs-- if just for a split second. Pitchfork: Why do you think more musicians don't write about being musicians? Recently, self-reflexive rock music seems to be all the rage, but it seems fairly logical that musicians would be interested in talking about making music. DB: Most musicians don't write about being a musician cause most musicians aren't writers. I also don't think that it is a worthy subject in and of itself. Really good musicians don't think of "self-reflection" in those terms. I can't really comment on all that, since I'm not really a musician. Anyway, the staying power of these themes seems unproven. They seem like a good springboard to other concerns, at best. Pitchfork: I was reading an interview with you where you described making music as presumptuous. It seems as if Destroyer's Rubies is the first album where you're kind of embracing that, having fun with it, maybe even hamming things up a little. Are you less self-conscious about your role as a musician? DB: I think the more removed I feel, the more I warm up to the role of singer. I used to struggle a little bit with the idea of how to separate singing from acting and entertaining- now I don't think about it so much. The more I abandon ideas of myself as a musician, the better a singer I become. For instance, I don't think I've ever hit less notes in my life, yet I think Destroyer's Rubies probably [has] the best set of vocals I've recorded. Everyone else in the band is coughing up so much melody, that for the most part I felt pretty free to do whatever I wanted with the words. Pitchfork: Are you more comfortable with your own voice now? You seem a lot more expressive and less hesitant. Your pronunciation seems to have changed, also-- fewer "h" sounds before vowels and more "I" pronounced as "uh." Does that have anything to do with anything? DB: I think the changes are ethnic shifts. Or maybe religion-based. Like I said before, once you feel like you can safely quit a melody, you are free to explore more important things. Someone in the band said they thought the world of phrasing is really untapped, and I think, not just out of the idea of self-preservation, that I must agree. It's some of the most unexplored pastures in rock music. Pitchfork: Ethnic or religion-based shifts? DB: I guess I was thinking of steering into nomadic singing-- you know, gypsies and Jews. Bejars were Sephardic way back, you know. By "religion," I just meant "prayer" or maybe the sound of some kind of daily composed grieving...Is that what you meant? Also, I think the "h" was a product of me desperately trying to project melody, while the "I" and the "uh" is the sound of me replacing the feeling of needing to project melody with the feeling of needing to drop cues to the listener about listening to the word that I just finished singing. My hunch is that I'm better at the latter. Pitchfork: The production on Destroyer's Rubies seems a lot more intricate and deliberate than it has been on past records. Were you trying your hand at "playing the studio as an instrument" or something to that effect? Did you have more time, money, and human resources to devote to recording this album? DB: The production seems to me warm and lush and pretty focused on just making the band sound good and having everything sit well together. [Producers John Collins and Dave Carswell] have just really honed their chops over the years and are really good at what they do. There are some songs that really came to life in the mixing process, like "Painter in Your Pocket" and "Rubies". But compared to Your Blues, which was an exercise in "playing the studio as the only instrument," it was all relatively straightforward. Pitchfork: I realize you probably wouldn't be so gauche as to trot out a Neutral Milk Hotel reference, but the stark acoustic guitar and getting-up-and-leaving sounds at the end of "Rubies" reminded me a lot of the end of In the Aeroplane Over the Sea. DB: I think there is a mystic element, and a sustained tone of catharsis, in Aeroplane that is absent in Destroyer's Rubies. It's more likely that I had somewhere in the back of my mind the end of [the Plush album] More You Becomes You, but really I just wanted to get the sound of me playing in a room and then not playing in a room. Pitchfork: From what I've read, This Night was pretty hastily put together, and Your Blues was aesthetically very different from your past albums. Were you at all concerned about putting something together in a more conventional "rock" paradigm? Destroyer's Rubies, which has been really well received, strikes me as having a lot in common with This Night, which was not very well received. DB: Well, that's a tough one. I think there's a lot more in common between Rubies and This Night, than say Streethawk. This Night was pretty indicative of where Destroyer songs were headed. The guitar playing is pretty distinct, so I think it just has to be audible in the mix and it's going to define what you're doing to a certain degree. This definitely holds true on the new record. I also think This Night wasn't as maligned as people think. It got trashed in Pitchfork, but there were some supporters and writers who in turn thought that Your Blues was really half-assed and goofy and a saccharine cop-out. This Night came together pretty quickly-- we probably could've used more than four or five days to mix the whole thing, but that's all hindsight. It's still my favorite Destroyer record, and has been since we recorded it. Pitchfork: Your songs keep getting longer and more complicated-- are you spending more time thinking through song structure? Consider this the obligatory "starting your album with a 10-minute song" question. DB: I don't know if they're getting more complicated. The dynamics have become subtler, less structural. I spend less time than ever thinking about parts, compared to a record like Thief, which has all sorts of little changes and aside-progressions. As far as long songs go, "Notorious Lightning" is a long song, and had I had the guts back then I would've started Streethawk with "The Bad Arts", so I guess maybe something has changed after all. There was a lot of shit I wanted to say in "Rubies", and I wanted to say it as close to all at once as possible. I don't really see it as one of the key songs on the record, though I like it, and I actually get a kick out of playing it live, which I didn't think would even happen. Pitchfork: Do you think carelessness is sometimes mistaken for genius? DB: I think it's way harder to assert yourself through carelessness than through rigour and precision, if that's what you mean. Hey, what are you getting at anyway!?! Pitchfork: Actually, I think that precision is one thing that consistently lands your work in the "critic's darling" camp, as opposed to an Arcade Fire or a Wolf Parade or something. Sometimes I feel like people want to hear artists pretending that they didn't think through what they're singing and playing-- maybe this speaks to the musician/writer distinction? DB: Well, now that you mention it, most of Destroyer work is instinctual, though at this point I think my instincts are strong enough to separate the things that work from things that don't. Your Blues and Streethawk are pretty precise, but a lot of the precision comes from John Collins. I think I have an ear for phrasing and words that manage to sound cool yet hopefully not go "clunk," and I think I know when to steer clear of a vocal melody that is totally hack, but after that things can easily veer into awkward and messy territory. I guess my guitar parts are usually precise, but the execution of those parts is downright treacherous, since I'm not very good on guitar. Pitchfork: I guess I was talking more about the writerly/lyrics side of things. Your lyrics-- and Carey Mercer's-- never sound unintentional or disembodied or "transcendent" or something. Of course, no lyrics are ever unintentional, but I think bands like Wolf Parade and the Arcade Fire have a tendency to touch on big themes without really following through on them or tying them in to a particular logic. Big, evocative words get thrown around, and people can sing along passionately as if the lyrics just materialized out of the ether, largely because they don't ever seem to coalesce into a writerly voice. You and Carey, on the other hand, always seem very present (as writers, not characters) in your lyrics. DB: Umm, I see what you're saying now...And agree wholeheartedly! I don't think there's much of an after-the-fact feeling to my writing, or to Carey's for that matter. People say I write specifically about nothing in particular. I don't know about the latter part, but I think the first part is really important in conjuring up a voice that works, or at least the illusion of a voice at work. I think Destroyer writing, whether it's good or bad, or operates at the expense of the music, at least adheres to its own logic, fairly consistently, which is all that you can really ask of a world, aside from maybe that that world be good or beautiful. But you gotta wonder if this very "present" style of writing is forever at odds with truly gelling with the music, and that a more vague or transcendent or heroic style is better for losing yourself in it all. Part of me likes words as music sabotage, and part of me wonders why anyone would waste their time liking anything to do with sabotage. With Frog Eyes or the Clientele, the sound being whipped up and the words being spat out or cooed all seem to be part and parcel, which is probably the ideal way of being, and probably something that just comes about naturally. That being said, some of my favorite writers, like Cass McCombs and Azita, achieve a way more awkward and precarious balance, and that's cool too. I would probably place myself more in that camp-- or the Babyshambles camp, if they would have me. Pitchfork: With a more permanent band in place, are you planning to do more extensive touring? DB: I intend to do less touring than ever. We'll see how these intentions get thwarted. I think the Merge showcase we played at the 2002 CMJ, during the This Night tour, might have been the best Destroyer show ever, and people still found a way to talk shit about that performance. My good shows were in Chicago, Detroit, and Chapel Hill, for those keeping track. A great live band is usually U2 or Bruce Springsteen or some other shit I could care less about. When anyone's talked about an ultimate "religious" experience at a rock show over the past 30 years, it's in reference to bands like that. When people talk about "great energy" or an "intense live experience," it would always be talking about the Fugazi show, not the Pavement show. People go to church at a Clash show, not an Only Ones show. And I think this ties in a lot to that ramble above that you got me going on, about the specific vs. the transcendent. Things usually have to be balls-out rockin or brood teetering on the verge of collapse. It's quite possible that if you're not interested in creating cathartic moments for the audience, both you and your audience are fucked, to which I say, "Oh well." No one appreciates a professional anymore. Everyone's a mystic. Which is why I take drunk Jim over acid Jim-- the argument all roads eventually lead to. Pitchfork: I see what you're saying, but I think there's the other side of the transcendent live show spectrum where you feel like you're getting a glimpse of a specific artist at work. I was pretty blown away by the acoustic shows you did in New York right after Streethawk came out, and I know a ton of people who've said "I saw Pavement this one time and it changed my life." People also go to shows to get a "real" glimpse at someone whose songwriting is intriguing and perhaps even a bit mysterious-- which is maybe why I've heard some people express disappointment that you don't banter more. DB: You were also that age where music has no choice but to loom way larger than it can possibly loom for you now. When something is operating at that level, it's always more special. I don't banter with the audience, cause I don't have anything to say to them, and I'm not feeling any sense of ease or camaraderie when I'm on stage. When I'm watching something as part of an audience I've never desired that from the thing happening on stage, so it doesn't occur to me that anyone else should either. Pitchfork: I think the "professionalism" that gets in the way has more to do with the clubs as it does with the performers. I've seen a ton of really high-energy shows fall totally flat-- I can't imagine seeing anything at Avalon in New York, for example, that would qualify as a "religious" experience, even though Avalon is a church. Maybe this is just my own growing out of teenage fanboydom, but it seems like rock shows are more church-like now insofar as people go out of a sense of vague obligation and maybe throw a few bucks in the collection plate. DB: I forgot that element of the church-- the element of drudgery and ritual. I know what you mean about professional rock clubs in the bigger cities. My favorite shows are usually in saloons where maybe some people are out to see you but most are just out cause it's Friday night in Moorhead. Pitchfork: This is sort of a weird comment, and I hate to drudge up the overplayed Bowie comparison, but I think it's really funny the way you refer to the "kids" versus the way Bowie referred to the "kids." He was like, "Hey, the kids! I know what the kids are hip to!" and you come off more like...a crotchety uncle? DB: Well, to be fair, I think if Bowie had been singing about "the kids" in 1981, he might have sounded like someone's uncle as well. I was born in 1972, which means that in "rock" terms I have no business addressing "the kids" unless it's to shoo them out of my garden.

|

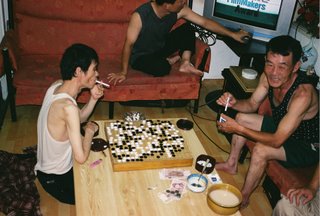

Here is Hoops, looking like he isn't sure he likes what he is eating (Sushi and noodles on New Year's Eve). Dan is digging it, though.

Here is Hoops, looking like he isn't sure he likes what he is eating (Sushi and noodles on New Year's Eve). Dan is digging it, though.